A long, long, time ago…

...Shortly after the discovery of America, there was a plethora of wonderful products of the new world brought to Europe. Among them, was a Mexican wood supposed to be efficacious as a diuretic and therefore called “lignum nephriticum” (palo azul).

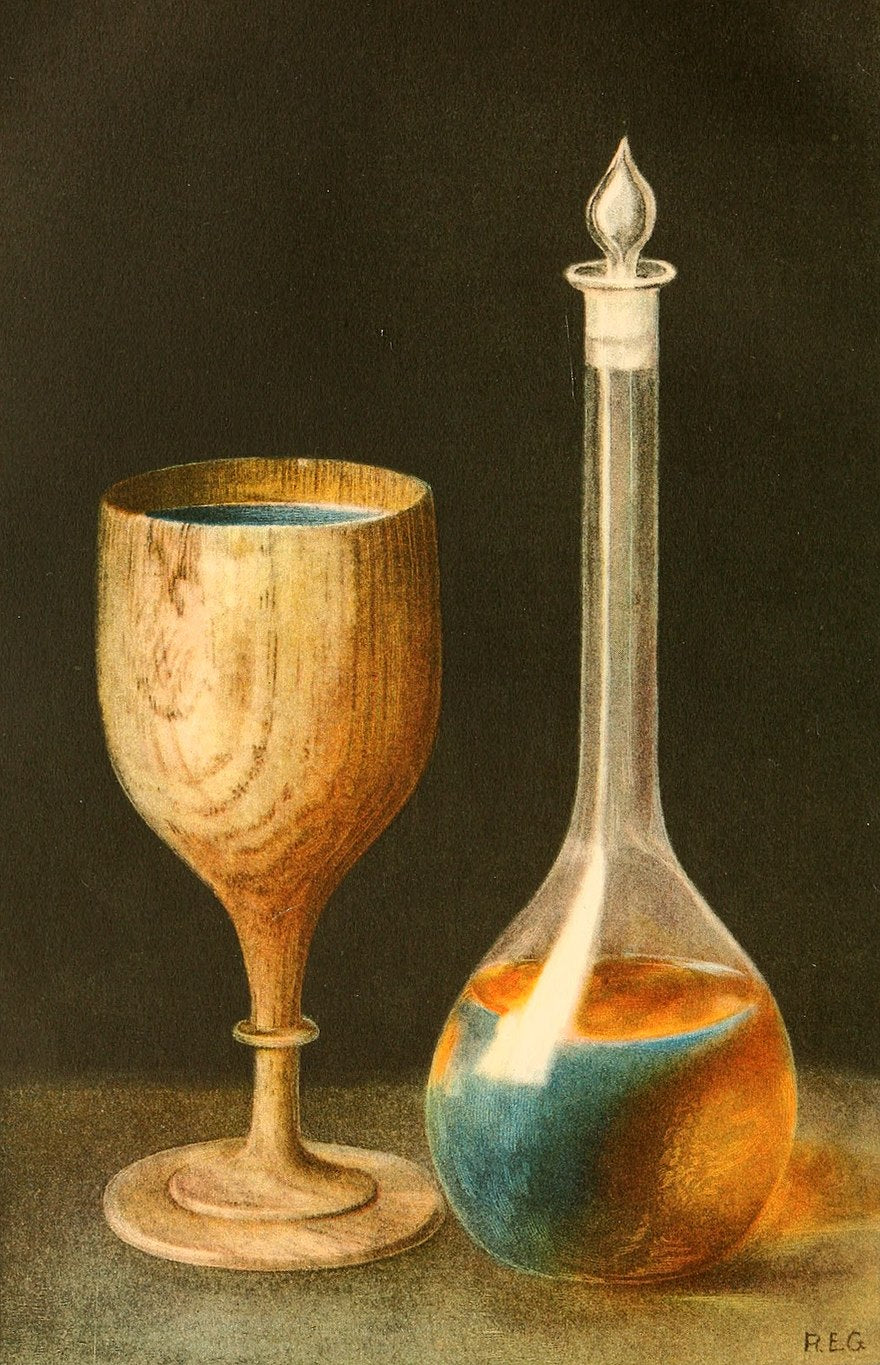

When left in cups of water, the infusion of this plant had the remarkable property of reflecting a blue color. This property came to be known as the phenomenon of fluorescence, and it was so surprising at the time, that it was studied by one of the greatest scientists of all time...Isaac Newton! And 300 years later, it was studied by Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone and founder of AT&T!

Fluorescence was Discovered in Palo Azul!

In fact, the books "Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences" and "Early History of Solution Fluorescence" both mention that the phenomenon of fluorescence was discovered for the first time in palo azul!

Perhaps even more fascinating...an article mentions that because of palo azul's supernatural beauty, cups of this tea "were given as gifts to royalty." The article mentions that Athanasius Kircher, considered to be one of the fathers of the science of fluorescence, "presented the cup to the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand III." Now we feel like royalty drinking our palo azul tea!

Lost for 300 Years!

The first botanical description of palo azul was very confusing and the full description was never found. Because of this confusion, the palo azul plant was lost for 300 years without being identified! And thus, the search for the true lignum nephriticum had begun.

Dozens of scientists attempted to search for palo azul and they encountered countless mishaps on the journey to find the true source of lignum nephricitum (palo azul). Special thanks to William Safford, for rediscovering the true source of palo azul in 1914 and for writing about the quest.

Identifying the True Palo Azul

Hernandez (1576) was the first to establish a botanical description of this plant, which he described under the name “coats, or coati.” He was a physician rather than a naturalist, and many of his descriptions and illustrations of plants tended to be crude and almost unrecognizable.

He was uncertain regarding the plant producing it, stating that it was described to him as a shrub, but he had seen specimens of it exceeding a very large tree. Hernandez’s work never appeared as a whole and for 2 centuries the plant remained unidentified botanically. And thus, the search for the true lignum nephriticum had begun, so get ready for a magical and surprisingly unexpected journey through time.

In the attempt to make the story easier to follow, below we have provided bullet points for each different event in the attempt to discover the true lignum nephriticum.

Dozens of Scientists Searched For It

• Caesalpinius (1583) and Caspar Bauhin (1623) supposed it to be a species of a plant called Fraxinus.

• John Boeclerus (1745) believed it to come from a tree called Laburnum, and called it Cytissus mexicanus.

• Then, Linnaeus, in his Materia medica (1749), added to the confusion by referring to it as Mooring pterygosperma, an East Indian tree, in spite of the fact that it was originally declared to be of Mexican origin.

• Nearly 70 years later, Guibourg, in his Histoire abrégée des drogues (1820), identified it with the West Indian cat’s-claw (Mimosa unguis-cati L.).

• Dr. Leonardia Oliva, Professor of Pharmacology in the University of Guadalajara. He was the first to indicate its true botanical classification in his Lecciones de Farmacología, where he identified it with Varennes polystachya DC. And just as this revelation came, it was subsequently dismissed by authorities who did not accept his identification.

• Dr. Fernando Altamirano (1878) recognized that the identity of the lignum nephriticum of Hernández came from the tree called by the modern Mexicans as palo dulce and referred as Viborquia polystachya Ortega, but he was not aware that the latter was the same as Eysenhardtia amorphoides H.B.K. Because of this mishap, he mistakenly followed another scientist, Alfonso Herrero, in identifying lignum nephriticum as Guilandina mooring.

Eysenhardtia Polystachia

Safford, William Edwin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

• Sargent, in his “Silva of North America,” gave an amended description of the genus Eysenhardtia, in which he for the first time established the combination Eysenhardtia polystachya, but he had no idea that this species had anything to do with lignum nephriticum, or that its wood yielded a fluorescent infusion.

• Hanbury had been seeking for lignum nephriticum for years, but had no success. Both Hanbury and Flückinger published their well known “Pharmacographia (1879),” but chose to be silent about lignum nephriticum.

• Dragendort, refers to it as a species of Guajacum. However, he was influenced by Ramírez and Aclocer’s “Sinonimia vulgar y científica de las plantas Mexicanas” (1902), and so he referred to a piece of wood in the Paris Exposition which was labeled “cuatl” and identified it as Eysenhardtia amorphoides; but the wood was unaccompanied by botanical material by which it might be identified with certainty.

• The last author to investigate the origin of lignum nephircitum is Dr. Hans-Jacob Möller, of Copenhagen, who after an exhaustive study of the wood referred to it as a Mexican tree belonging to the genus Pterocarpus. Dr. Möller carefully examined various woods that were allegedly supposed to be the true lignum nephirticum mexicanum.

Among them were specimens of the wood Eysenhardtia amorphoides, but it reported negative results. He then examined the heartwood of a Philippine species of Pterocarpus, and he found that in water containing lime, it yielded an infusion having the characteristic sky-blue fluorescence of lignum nephritic mexicanum as described by early investigators. He therefore assumes that the mother-plant of lignum nephritic mexicanum, “sought in vain for 300 years by so many investigators, is a Mexican species of Pterocarpus.”

Safford, William Edwin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Möller Confused it With Pterocarpus

Dr. Möller thought that palo azul was a species of Pterocarpus, but the leaflets of the species of Pterocarpus figured by Möller himself exceed 6 cm. in length by 3.5 cm. Hernandez described the leaves as “resembling those of Cicer arietinum [chick-pea] but smaller,” and also compared them with the finely divided leaves of the common wild rue, therefore it cannot possibly be identified with any known Mexican species of Pterocarpus. So the search continued.

Hernandez Described 2 Different Species

To further add to the mystery, Hernandez’s original description of lignum nephriticum actually described TWO different species! It is as follows: “They call coati a plant which they describe as a shrub; but I have seen it larger than very large trees; and some call it tlapalezpatli, or blood-red medicine.”

The first, with leaves resembling those of Cicer Arietinum [chick-pea] and with spikes of small longish flowers, is undoubtedly Eysenhardtia polystachya, which never exceeds the size of a small tree. The second is in all probability a species of Pterocarpus, which grow to much larger dimensions than the Eysenhardtia.

Sought for 300 Years and Finally Found

William Edwin Safford had been seeking the source of lignum nephriticum for years. He examined specimens of Eysenhardia polystachya that he collected in 1907. The infusion however, gave no evidence of fluorescence in ordinary sunlight and the specimens that he had seen were either shrubs or trees too small to yield wood for the manufacture of bowls and cups. For this reason, he was inclined to agree with Möller in discarding Eysenhardtia as a source of the famous wood.

Safford, William Edwin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

That was the case until July, 1914, when specimens of a medicinal wood from Mexico were brought to the writer along with herbarium material from the same tree sufficient to identify it. The individual who brought them hadn’t noticed anything about the color of its infusion, but dwelt upon its efficacy as a cure for certain diseases to which fowls are subject in Mexico. This wood proved to be the famous Eysenhardtia polystachya, commonly known by the modern Mexicans as palo azul or palo dulce (sweet wood).

This is Safford's description of palo azul’s glow: “A few small chips of the heartwood in ordinary tap water tinged the latter a golden yellow, which soon deepened to orange, and looked like amber when held between the eye and the window. When the glass vial containing the liquid was held against a dark background the liquid glowed with a beautiful peacock blue fluorescence. Placed party in a sunbeam, half of the liquid appeared yellow and the other half blue; and when sunlight was focused upon it by the lens of a common reading glass, the vial appeared to be filled with radiant gold penetrated by a shaft of pure cobalt.”

There was no longer any doubt as to the identity of the wood. It could only be the true lignum nephriticum of Robert Boyle’s experiments; and it was undoubtedly the wood of Eysenhardtia polystachya.

Illuminated Their Faces

Following this event, the author went to the house of the famed scientist and inventor Alexander Graham Bell on the evening of January 15, 1915 and presented to him the specimens of the wood. Safford describes: “Specimens of the infusions when exhibited by ordinary electric light failed to show fluorescence; but afterwards, when held in the rays of an arc light the liquid glowed with intense blue which illuminated the faces of those standing nearby.”

The End!

For the first time in nearly 300 years, the identity of the true lignum nephriticum which Hernández originally described had been established beyond a doubt. Its characteristic fluorescence corresponded accurately with the descriptions that Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle obtained in their experiments about fluorescence. After dozens of scientists attempting to search for it, the true source of lignum nephriticum - Eysenhardtia Polystachya - palo azul, was identified. Finally, we can all enjoy the most magical tea in the world.

Sources

Palo azul's scientific and common names: Eysenhardtia polystachya, Cyclolepis genistoides, Lignum nephriticum, kidneywood, kidney tea, palo dulce

(1915) Eysenhardtia polystachya, the source of the true Lignum nephriticum mexicanum

Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences

(2007) Early History of Solution Fluorescence: The Lignum nephriticum of Nicolás Monardes

Hi Sigrid, we have actually looked for cups made from palo azul wood but we haven’t found any. We will figure out how make them though and get back to you!